Over 29 days I had travelled 15,000 km, starting in Glasgow and going across Russia all the way to Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk. Some of it has been good, some of it has been great, but at the end of every chapter there’s a bit of reflection, and as I sit here in the departure area of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk airport there’s a fair few thoughts going through my mind. It’s hard to really describe what my expectations for the city were; written material about it usually focuses on the oil and gas industry, or on the nature and scenery, and you get the odd mention of Chekov’s journey and his brutal description of the place. Perhaps with that in mind I expected to see a bit more vibrancy and wealth on show in the capital of the island, or at least some kind of energy and excitement about the place. I’d been told at different times it was expensive, or full of expats, or an island with increasing revenues to spend on the place…but that’s not what I found here.

I’m getting used to flying into minimalist regional airports in Russia, getting onto the bus and sitting in a cramped seat for at least half an hour, and Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk was no different. The sky was grey and rain was threatening, but it looked like I had avoided the storm that battered the island only a few days before. Evidence of its impact was everywhere, from trees and branches strewn across pavements and streets, to bus stops that had been mangled and blown over walls. However the city lived on, the buses ran, people found their way to work, and shops were open as normal. I would be staying with a guy called Maxim in the city, he works for an international company and was kind enough to offer me a room for a couple of nights. I dropped off my bags with him and set out to explore the city on foot, though I’ll admit I wasn’t too impressed with the weather on this occasion. The conditions were as close to Scotland as I’ve come across in Russia, with temperatures at 7C at the best of times, with gusts of wind and the odd shower of rain a constant presence. My first impressions of the streets were a sense of depression and sporadic development; the pavements were non-existent at times or lost beneath decades of muck, other times there were gaping holes every few steps. Dirt and debris covered every roadside and cars would speed past missing parts of their anatomy. I can accept that the storm caused damage and a lot of the debris is likely from that, but the rest has been there for the long-term and really is in need of repair. Whatever the money from the Sakhalin projects is being spent on, it’s not fully making its way to the benefit of the general population. I continued walking away from the main streets of the city, hoping to see some of the Japanese architecture that is said to remain, but even this seemed an exaggerated claim at best; some of the sites I visited were crumbling. I tried the botanical gardens, but the storm had seen it having to close for a while. A walk through Gagarin Park was a mixed bag; the storm had damaged a few kiosks and rides, but it’s hard to imagine great weather bringing much more beauty to the area. As I walked back towards the centre from the north, the streets blurred into a mish-mash of decrepit wooden buildings and peeling flats covered in Soviet murals from yesteryear. I began to wonder if I was entering the local equivalent of a favela. Maxim would later tell me of an area called ‘Shanghai’ which in the 1990s was the hotbed of crime and poverty in the city, though there is at least a greater sense of safety than in those days.

As I headed back to meet Maxim I had started to completely write the city off as a dead-end, that the city could turn up all of the Tsar’s missing gold and it wouldn’t make a single difference to the development of the city. I tried to remind myself that you can’t just fly into a city for a few hours, make a quick judgement and head off again with a few sensationalist headlines. For all the negatives I had seen, I wanted to find positives amidst the gloom, even if it was only one or two. At worst, I would be able to tell myself I had given it a fair crack of the whip. Maxim’s grandmother cooked a meal for us, and I’ll give my compliments to the chef as it’s one of the few times I’ve been satisfied with a bowl of cabbage soup. I asked him about his life in the city, he told me that he was born and raised here with a few spells abroad including the USA and China, and had been to Europe a few times on holiday. He told me that although he still likes Europe and the UK for music and culture, he was comfortable living in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk and was in no rush to move. I enquired about the reasons why, usually those who are such big fans of foreign cultures want to go there, but he described a sense of local pride. It was in sync with Russia, but people had their differences. At this point Alexei arrived and he added to it, feeling that the sense of humour in the city had differences to that in the west of the country, more intelligent and less direct. He said people on the island were more hospitable and helpful than the mainland, with people willing to do a favour even for someone they didn’t know. I won’t pretend to know for sure if that’s the case, but the next day we would see an old woman lying on the ground, and there was no shortage of help and a willingness to stay with her until help arrived, despite lots of those workers previously rushing to make it to the office by 9am.

After dinner we went on a tour of the city, taking in a few of the local monuments to the war heroes, the Lenin statue and best of all a trip to the top of the nearby hills for a view of the city. In the winter the place turns into a great place for skiing and snowboarding, with both Maxim and Alexei telling me it rivals nearby Sapporo for the experience. We would then meet Katya and head off for Korsakov. I asked them about the Japanese cars, and the fact that many vehicles seemed to be bashed, broken or looking the worse for wear, and they told me, quite expectedly, that the second-hand car market here is huge, with most cars from Japan, some from Korea, and even fewer from Russia. However the run-down nature of the cars is because everything delivered to the island is raised in price, even from the Russian mainland. Maintaining a car in perfect condition can be an expensive business, especially with the poor quality of roads. Maxim in particular wasn’t too happy about the degradation of the roads, and it’s something the city really needs to sort out. Korsakov itself is dominated at night by the flaming gas and the lights of the facilities. You can see tankers creeping out or arriving from Japan, and there are usually a few people at the peak of the town looking out on the view. If you’re ever in town it’s something to do when the sun goes down.

We talked more about the development of the island, and all were in agreement that it was lopsided and usually the benefits were in areas important to the gas industry. This I can understand, international companies don’t get into business for the benefit of the average citizen, but it sounded like the regional government had work to do to win over the hearts of the populace. There didn’t seem much optimism about seeing results, though I should add that it didn’t make them want to leave, they still felt comfortable here despite the problems. I asked my obligatory question about the fortunes of the local football team, FK Sakhalin, who had just earned promotion to the second tier of the Russian system, and with it a crazy schedule of matches stretching as far away as Kaliningrad; they weren’t too interested in the team. Football just didn’t seem too popular in general; even hockey was of limited interest for the league on the island. People were more interested in individual sports, winter ones in general, and the forthcoming World Cup matches were more of a novelty than a deep concern. I took a walk to the stadium the next day; it’s a really small place with one stand and it’s hard to imagine it hosting bigger games next season, though it had strong links with local youth programs which was good to hear.

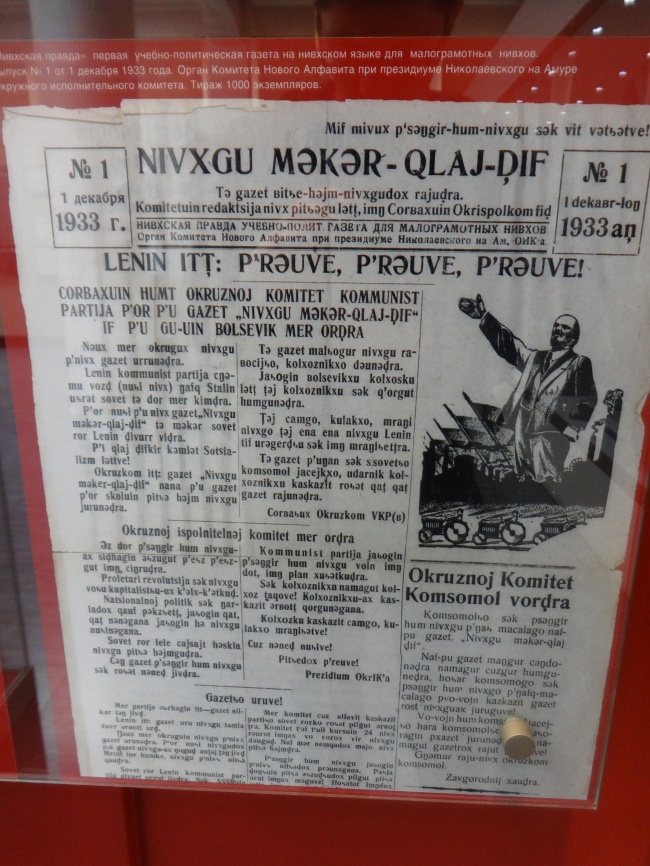

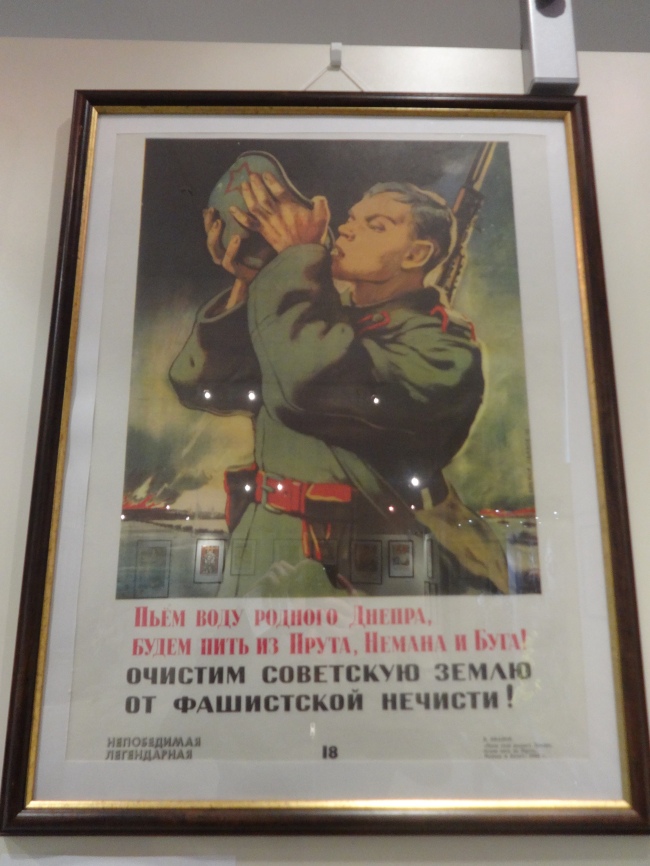

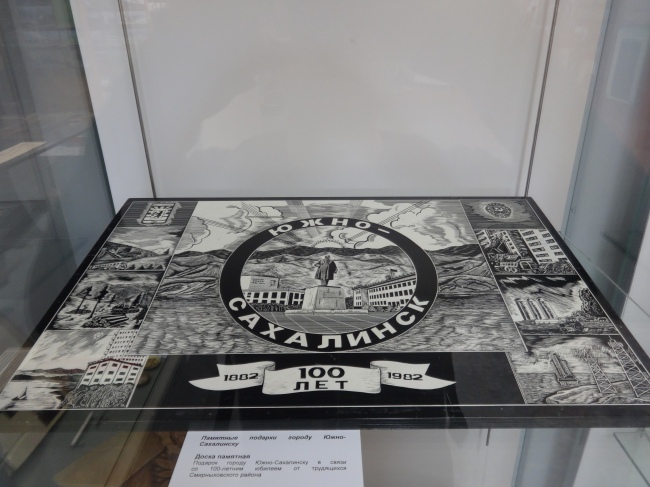

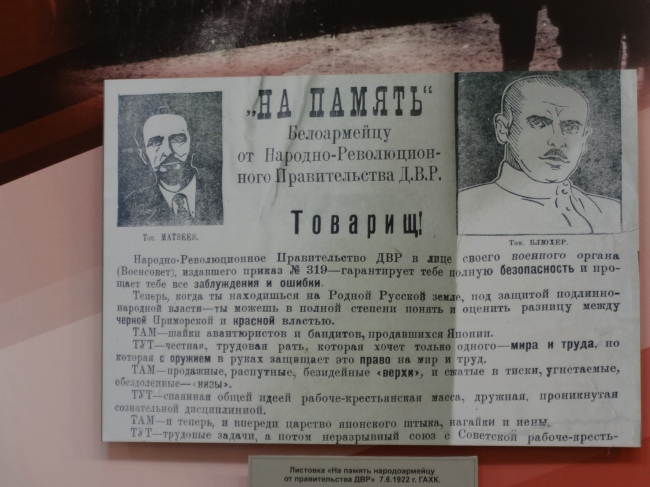

The weather the next day was just as dismal as the last, but I endeavoured to keep up my walking and reach the 10km mark. I paid a visit to the regional museum, set in an old Japanese building that really is a marvel on the eye. The grounds were kept in great condition despite the storm, with only a few signs of disturbance. Inside there’s two floors, covering some fauna and archaeology at the bottom, through to exploration of the islands and life during and between the wars. It’s not the biggest museum I’ve ever been to but it’s definitely the best one on the island and worth a visit. If nothing else the price is an example for all of Russia, 70 rubles to get in, no extra cost for foreigners and 100 if you want to take pictures. Afterwards I tried the local art museum, with some interesting work there from a local artist and even a room of works by North Korean artists. However if you come here as a tourist be aware there’s a very limited amount of things to do and see. Even the local brewery had shut its restaurant doors, and many cafes or restaurants never opened before lunchtime. Either you live and work here, or you find yourself a hobby during your visit and get out to see the surrounding nature.

I met Maxim and Alexei again, as well as a few others, and this time we went out for a beer. They opened up a bit after a while and I began to get more of an insight into the local culture. There was a good sense of solidarity as I had begun to see earlier, and people looked out for each other. However the one thing I had noticed on the streets was the divide between the Koreans and the Russians. There was a bit more mixing than in Yakutsk, but there was definitely a divide there. I asked the group about it, and they agreed that there was a social divide between the two races. The Koreans were born here, they spoke Russian, but they still retained their own cultural preferences, the social structures still related to the Korean mainland, and the Russians could feel that. Not that they complained or held resentment, they understood it as normal, different peoples have different ways of life. There was a bit more resentment for immigrants from Central Asia, though it wasn’t as strong as I’ve come across in other Russian cities. The numbers are very limited and hasn’t reached any sort of tipping point, and interestingly enough a number of construction works have North Korean workers here. I didn’t see any, but I’ll have to take the group’s word for it that they’re there. Indeed one non-Russian group who got the most flak were Americans, with a disappointment that some would stay for several years and learn barely more than a few words of Russian in that time. The numbers are so small that it is unlikely to become an issue, but even here on Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk people like long-term visitors to make an effort. With the beers starting to add up we left the conversation there and called it a night.

With that my stay was at an end, the next day taking the lunchtime flight on to Sapporo in Japan. I’d like to offer firm conclusions and thoughts about Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, but I feel like I was only scratching the surface. The problems that exist there are very visible, possibly permanent, and I couldn’t imagine any Russian moving there unless it was for the energy and resource industries. At the same time the people I spoke with were comfortable living on the island, they had a basic sense of regional pride and there were a number of sub-cultures going on that just didn’t have any obvious outlet. Life will continue to amble along here no matter whether there’s investment or not, and perhaps appealing to foreign investors and even tourists is just completely unnecessary here outside of the nature and adventure tourists. What the island did give me was a few things to chew over about the Russian Far East in general, and I’ll try to approach those issues in future articles.

For now it’s on to Japan and a few other Asian countries. I won’t be posting the same articles as I have done so far, but I do aim to get talking to the natives and find out what people in Asian countries think about Russia and the Russians. It’s time to see Russia from the outside, through the eyes of others.